The Chemistry of Success: The Legacy of John K. Coleman

(This story was originally published in ‘E Roar | Vol. 2 Issue 1 in Jan. 2025)

By Jet Turner, Assistant Director of Communications

Dr. John Coleman received a call from the fourteenth president of Langston University, Dr. Ernest Holloway, in 1993. Holloway’s gregariousness led their conversation all over the place, but his message was clear: the students at Dear Langston needed additional support.

Coleman left his position as an assistant professor at Hudson Community College in New Jersey after that summer and journeyed back to his home state of Oklahoma. He only planned to stay for a couple of years, but his dedication to helping students be their best kept him on Langston University’s campus. After 32 years of service and mentorship, Coleman will retire at the conclusion of the 2024-2025 academic year.

His career as the Chair of the Department of Chemistry at LU has been dedicated to teaching science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) subjects and equally to seeing that students learn to excel in academics and life. His influence can be seen all over the University and, more importantly, in its students.

Beginnings

Coleman grew up around educational excellence in Boley, Oklahoma.

Today, the historically Black town might seem unassuming, but when Coleman was growing up in the 1940s and ’50s, the town was described by Booker T. Washington as the “finest Black town in the world.” Many of the individuals Coleman grew up around had their doctoral degrees or some other form of higher education, including his parents.

Boley’s significance in education parallels no other Black town in the nation, historian Currie Ballard said in a 2017 article by The Oklahoma Eagle.

This meant Coleman was always surrounded by excellent teachers. One of whom was Holloway, his future president, who taught chemistry at Boley Junior High in the 1950s.

“Holloway knew what was happening in Boley and how we got prepared,” Coleman said. “You always have someone who is going to help you. You didn’t have to rely on just your resources at home.”

Community is where Boley found its strength, and Coleman carried that lesson with him throughout his academic career.

Coleman always expected to go to college, and Langston University was a natural choice.

He began his freshman term during the 1961-1962 academic year. Buildings like Sanford Hall and Moore Hall still stood proudly where they are today, although their functionality was different from their modern day uses.

During his time at LU, he served as the freshman class president and was a brother of Alpha Phi Alpha Fraternity, Inc. Even though LU had been around for almost 75 years by the time Coleman graduated in 1965 with his bachelor of science in chemistry and mathematics, students still had to march at the Oklahoma State Capitol every year to fight for the university to remain open. Coleman was an active participant in these efforts.

Just as obtaining his undergraduate degree was expected for Coleman, working toward an advanced degree was a natural next step. He began his PhD in Theoretical Physical Chemistry at the University of Oklahoma in 1972.

OU was still integrating, and undergraduate Black students especially were facing discrimination at the hands of some students and employees. Coleman became a graduate advisor to the Alpha Phi Alpha chapter on campus during this time.

“There were cannons pointed south and all kinds of things going on,” Coleman said. “But we did a lot of things with students to try to help students feel more comfortable. We did a lot of tutoring. We did a lot of whatever, trying to make the students come in and be successful.”

Growing up in a Black town and attending a Historically Black University helped Coleman understand the importance of community. At every opportunity, Coleman shared that community with others.

He earned his PhD in 1976 and concluded his postdoctoral studies at OU in 1978.

Coleman was briefly a researcher at Halliburton Company before traveling east to become an assistant professor at several local institutions. First at Bergen County Community College in Paramus, New Jersey; then at City University of New York, and finally at Hudson Community College, where he received that call from Holloway.

Returning Home

Upon returning to Langston University, Coleman immediately got to work.

Coleman’s years of experience teaching STEM courses provided insights into the problems that frequently impede student learning. He encountered students’ wide-spread practice of what he calls “plug ‘n play.” Plug ’n play is when students use a solved “example” problem as a model and plug in variables from the new problem to find a solution. This bypasses the need to learn and apply core concepts.

Coleman developed and adopted instructional strategies embedded in a process he calls Competency Performance Recording for Learning (CPR-L). His CPR-L teaching and learning process has had a positive impact on student academic performance for his over 30-year career at Langston University and is the basis for how he approaches educating his students.

Dr. Alonzo Peterson, Vice President for Academic Affairs, witnesses Coleman’s commitment to Langston University’s students almost daily. Coleman can often be found on campus until 9 p.m. or later, depending on how many students still need help.

“He’s by far one of the smartest people I know,” Peterson said. “His ideas are very, very innovative. He spends a lot of time with students, hours and hours.

“One of the things I recognize from his tutoring processes is that he doesn’t give students answers. Students may ask, ‘how do you do this?’ and he responds, ‘well, how do you think we do it?’ And then he will go back and talk through the problem for them to solve it, not him. Some people are dispensers of knowledge, he is a facilitator of knowledge.”

In 2003, Coleman received a grant from the National Science Foundation which started Langston’s Integrated Network College (LINC) for STEM program. This program provided scholarships for students in STEM fields and required them to participate in research on campus and across the country. They would then present that research at conferences.

The goal of the LINC program was to produce more minority students in STEM fields who would then earn their doctoral degrees. This program was exceedingly successful.

LINC boasted a 92% graduation rate, with 60% of those students going on to earn graduate degrees. Many of these were earned at major universities that include Vanderbilt, University of Kansas, University of Texas, Baylor University, Johns Hopkins and more.

The students’ participation in summer research internships at institutions that include Johns Hopkins, University of Texas, Stanford, Cal Tech, University of California at Berkley, University of Oklahoma and more. Their research work generated over 300 Abstracts. Their participation in competitive research presentation events throughout the U.S. earned over 50 top awards.

These STEM professionals now hold prominent positions in both industry and education, including achieving success as entrepreneurs.

According to RTI International, of the STEM PhDs awarded in the U.S. in 2021, 5% went to Black scientists, even though the U.S. population is 12% Black, showing the disparity in the field.

Coleman was also encouraging students to stick with the STEM field, even if they did not think it would be for them.

Dr. Ryan Johnson, a former chemistry major and now professor at Langston University, was one of these students.

When Johnson began attending LU in the early 2010s, he was not interested in attending college, much less becoming a chemist. Even though he showed up to Dear Langston as an undeclared major, a mistake in the system had him listed as a chemistry major.

Wanting to change his major, Johnson was told to speak with Coleman before deciding.

That one conversation changed his life.

“He convinced me to stay,” Johnson said. “He told me I was doing well in my other STEM classes, and I was on track to take Chem I anyway. I took it the following semester and ended up staying with chemistry. Kind of weird, right? How those little conversations can change the trajectory of your life.”

As part of the LINC program, students had to at least apply for graduate schools as their undergraduate degrees concluded. Johnson had no intention of earning his doctorate, but another conversation with Coleman convinced him to apply to Louisiana State University, one of the leading producers of doctoral-prepared Black chemists in the nation.

Innovation was another one of Coleman’s missions in the classroom.

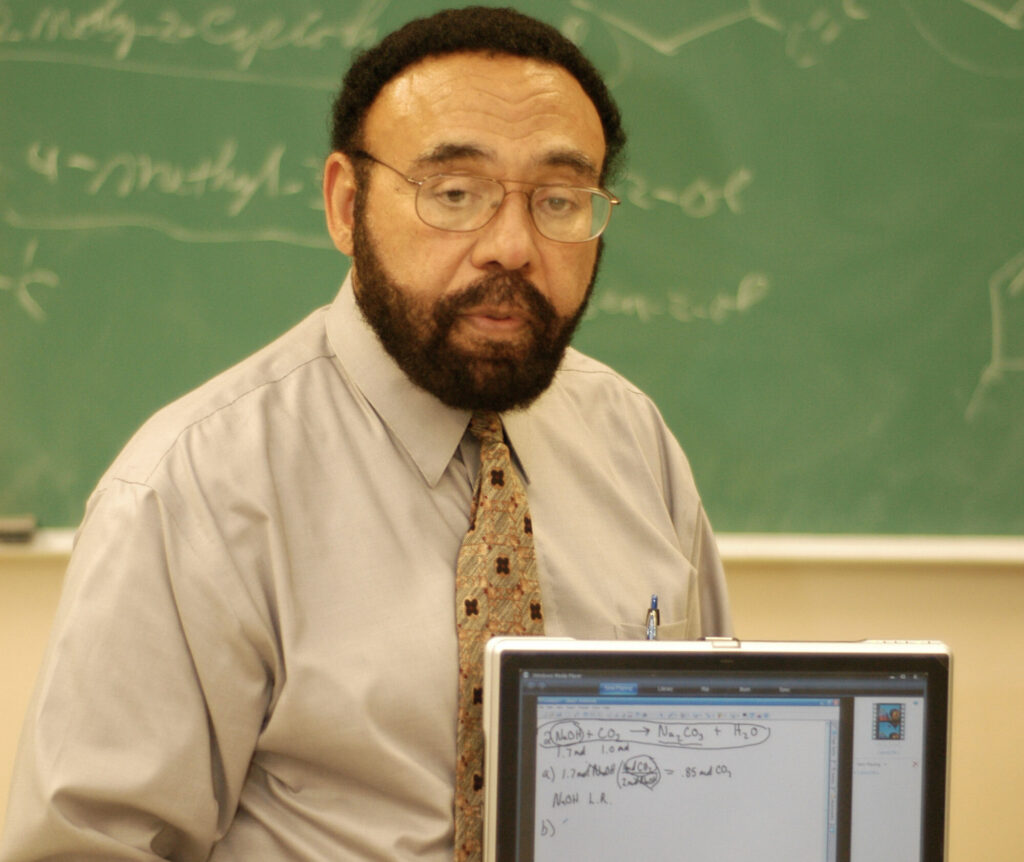

Coleman was an early adopter of integrating technology into the classroom at Langston University, something that stood out to Dr. Byron Quinn when he was being taught by Coleman at Langston University.

“Even back in the early ’90s, at the beginning, he was at the forefront of this,” Quinn said. “He was working with really the first iteration, first generation, of tablets and PCs in the classroom, so that students could write and do homework on them and digitally turn them in.”

But Coleman’s impact is much farther reaching than the borders of Langston University’s campus.

About a year after his return to teaching at LU, Coleman set out to build strong science and math foundations when he received a grant to establish the Langston University Summer Math and Science Academy.

It was here, when she was 14 years old, Dr. Lindsay Davis met a Black chemist for the first time in her life.

She hated chemistry.

“It was the hardest thing ever,” Davis said. “But Dr. Coleman had such an eloquent way of communicating chemistry. And so, by the end of that camp, I knew I wanted to be a chemist.”

She attended the Math and Science Academy many more summers after that. Her familiarity with the campus, its scholarship opportunities and its faculty led Davis to enroll at Langston University.

She took her first class with Coleman, Organic Chemistry, her sophomore year. It is still the most difficult course she has ever taken.

More than a third of black STEM PhD holders earn their undergraduate degrees at HBCUs according to American Institutes for Research.

But Coleman’s student-centric approach helped her through the class. She took three more classes with him throughout her time at LU and, after graduating, like so many of his students, was convinced by Coleman to pursue her doctoral degree.

“That took a lot of convincing, and there were a few mechanisms that helped me to go off and produce my PhD,” Davis said. “But Dr. Coleman being the first chemist I ever met inspired me to get a PhD.

“When you are able to see the representation in front of you, I think it either consciously or subconsciously inspires you.”

Because of Coleman’s influence, in 2021 Davis went on to become the first Black chemist to graduate with their PhD from the University of Texas at Arlington.

Legacy

Johnson, Quinn and Davis are just a handful of the students Coleman not only encouraged to go and earn their doctoral degrees, but to come back and teach at Langston University.

Quinn is currently the Chair of the Biology Department at Langston University, working closely with Coleman each day and utilizing the lessons he learned in using technology in the classroom to instruct his students and conduct world-renowned research.

Johnson just returned to Langston University as a professor in the chemistry department and is now providing the same mentorship, guidance and expectations Coleman gave to him as a student.

Davis is not only a professor in the chemistry department but also leads the Math and Science Academy at Langston University, bringing her journey full circle. Now, she gets to be the same inspiration to the students who attend each summer that Coleman was to her as a teenager. She may even be the first Black chemist some of them meet.

“I hope I even have (a legacy),” Coleman laughed.

But his legacy is unmistakable. Coleman has built his own community of educational excellence at Langston University, in the STEM field and across the world.

His mission has been to ensure Dear Langston’s students have the support they need to lay the foundation for a brighter future. Now, Coleman gets to wrap up his career as the Interim Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences, where he is still building programs and methods that will lay firm foundations and help educate students for the long term.

Langston University President Dr. Ruth Ray Jackson, who formerly served as the Vice President for Academic Affairs, has seen the impact of Coleman’s time at LU. She said regardless of his position, he has intentionally remained engaged with his students, ensuring they are well-prepared when they leave Langston University.

“I think that his lasting legacy really is his quest for knowledge, not just for himself, but for his students.

“We should all have a John Coleman in our lives.”